Throughout the history of textiles, few crafts have endured quite like knitting. Whenever we encounter knitted garments in shops or see someone speed-knitting on social media, it’s easy to forget that its legacy can be traced back many hundreds of years.

This intricate process of using needles to knit rows of interlocking thread loops together has created everything from socks (thought to be the oldest knitted item in the world) to hats, to baby clothes and much, much more, all in the name of keeping humans cosy.

Across cultures, communities and centuries, knitting has been both an enjoyable pastime and a practical way of creating warm clothing. The age-old artform has a fascinating history, so let’s unravel it stitch by stitch…

Knitting Through the Ages

While knitting has a rich backstory, it’s unclear to historians exactly when and where the craft first appeared in the fabric of time. Some say it began in the Middle East, while others trace it back to Egypt somewhere between the year 500 and 1200 AD. The V&A Museum in London holds a pair of knitted socks from Egypt dating back to between the 3rd and 5th century AD. Despite all this, the origin of knitting is open to interpretation as those socks were thought to have been made using a technique called 'nålbinding', or ‘nalbinding’, (the Norwegian word for “needle binding”), which is considered by some to be more closely related to sewing, rather than knitting.

When it comes to understanding its origins, part of the challenge is rooted in the rarity of ancient knitted items; over time, the natural fibres that would have been used back then have decomposed, leaving no trace of its existence. Nevertheless, the craft of knitting stands as a testament to human creativity, weaving its way through centuries with remarkable resilience, and passing skills down from generation to generation.

“Knitting is a way to connect with the past and create something for the future.”

– Stephanie Pearl-McPhee, author of Yarn Harlot blog

Evidence of knitting in the 1350s is clear from several religious paintings of that era depicting Mary—the mother of Jesus—knitting. Deemed to be an early depiction of the popularity of the skill among women, these paintings show Mary sitting on the floor, knitting a garment, titled The Knitting Madonnas.

The craft held a prominent role in mediaeval Europe, particularly in Scandinavian countries. Archaeological digs in mediaeval cities have uncovered items proving that knitted goods remained popular throughout the period and into the 14th century.

It was soon after this, in the 15th century, when the word “knit” first appeared in the Oxford English Dictionary, originating from the old English word “cnyttan” which meant to tie with a knot. Knitting and knitted items were incredibly popular in 15th and 16th century England, and were a valued part of the country’s economy – The Cappers Act of 1571 serves as proof. Introduced to support the domestic cap-making industry, the law stated that every person over six years old (with the exception of some members of society, such as maids, lords or knights) must wear a woollen cap on Sundays and holidays.

England continued to thrive when it came to knitting prowess, with the purl stitch thought to have been invented in the 16th century to create another garment that rose to popularity around this time: stockings. In fact, stockings were so popular that Queen Elizabeth I encouraged the formation of knitting guilds to meet the high demand. Her father, King Henry VIII, is thought to have been the first British royal to wear knitted stockings, but they soon became a wardrobe staple that cut across class; commonly knitted by both refined ladies and poorer members of society.

Knitting was even taught as a skill in orphanages, and there are records of knitting schools in English cities such as Leicester, York and Lincoln in the 16th century. In publishing, The National Society's Instructions on Needlework and Knitting (1838) was the first British book of its kind, dedicated to the craft of knitting. Whether enjoyed as a creative pastime, as a means to make personalised gifts for loved ones, or purchased as a finished item of clothing, knitting has never fallen out of fashion.

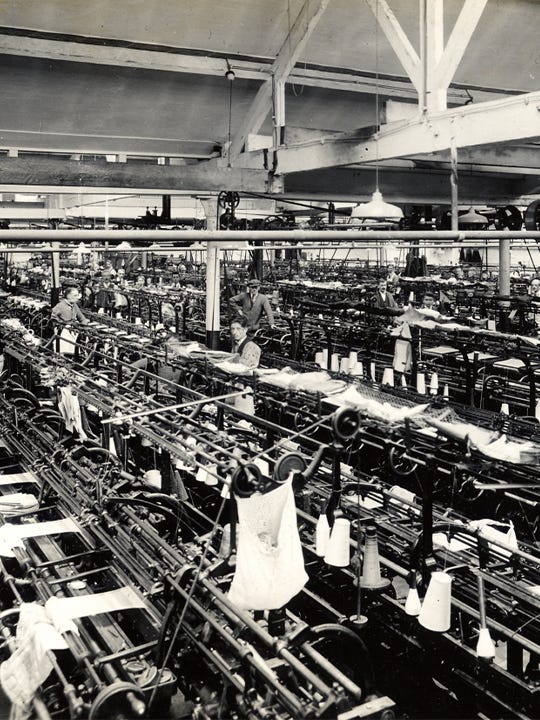

The Industrial Revolution

As with almost every handmade item, the advent of machinery brought with it the question, “how can we make this process more efficient?” Knitting was no exception, and so as the wheels of industrialisation started to turn, knitted garments went into mass production.

In 1589, a machine for knitting was created by the English inventor William Lee. Otherwise known as a stocking frame, this machine was the first device that mimicked the hand movements of knitting. Initially it had 8 needles to the inch and could only produce very coarse fabric, but over time the quality improved, and eventually the machine was updated to include 20 needles to the inch. Over time, cities like Nottingham in England became the primary producers of machine-knitted fabric, expanding the capabilities of their machines to develop things like the circular knitting machine and more. The country continued to innovate the ancient craft, and in the middle of the 18th century, the industrial revolution took this to new heights.

As the textile industry entered an era of unprecedented efficiency, skilled artisans of knitting were no longer able to keep up with the pace of the factories who continued to invest in innovative machinery. Much later, around the 1950s, synthetic yarns and fibres became popular which aided mass production, and knitting became more of a creative hobby and pastime rather than a necessity for warm clothing.

The Unwavering Popularity of Hand Knitting

When William Lee first developed the knitting machine in 1589, Queen Elizabeth I is said to have denied him a patent for the invention due to her concern for the security of the country’s hand knitters. Whether fuelled by worry over their jobs or the practice of knitting dying out completely, a sentiment for the protection of the art of hand knitting remains today.

Throughout history, hand knitters have made use of whatever tools were available to get the job done – hand-carved sticks, animal bones, quills, metal wire, or pieces of fine steel.

From the 18th century, hand knitting was taken up mostly by wealthier women who had the time to develop the skill, and during this time it was thought to be less about their need for warm, knitted garments, and more about the artistry involved. By the mid-19th century, knitting became one of the ultimate drawing room occupations, and as well as clothing, women started venturing into purses, pincushions, wall hangings and more.

Although knitting was enjoyed by everyone, women continued to dominate the pastime throughout history, with the Great Depression of the 1930s leading many people to make their own clothing. Later in the 1940s, hand knitting was a way for women to create warm clothing as part of the war effort during WWII.

By the 1950s, machine-knitted items became much easier to find, but by the 70s, hand knitting was back and a new attitude emerged; people were experiencing a revival in the desire for handcrafted goods. As such, hand knitting became more valued and sought after than machine knitted items.

The art of knitting is timeless and continues to be passed on from generation to generation. While just a few years ago it may have been considered a pastime of older people, today you will even find over 500,000 posts with the hashtag #knitting on TikTok, not to mention the emerging #KnitTok community creating lots of quirky and colourful garments. Its modern revival could be due to many factors, including its potential as a mindful practice in a very busy, noisy world.

The craft of hand knitting has managed to weave its way through the technological advancements of the modern age, and keep people excited about taking things back to basics, patiently crafting something by hand without the need for efficiency or productivity. Hand knitting perfectly preserves the connection we have to our traditions in a way machines will never be able to replicate, and this is true for many different cultures around the world.

Artisanal Disciplines

Part of the charm of knitting is the intricate details of its production, and the skill and discipline required to make a quality item. The repetitive nature of making stitches can be picked-up by most people, but there are many more artisanal disciplines involved in creating an item of clothing, such as linking different sections of the garment together, adding trims and other intricate details.

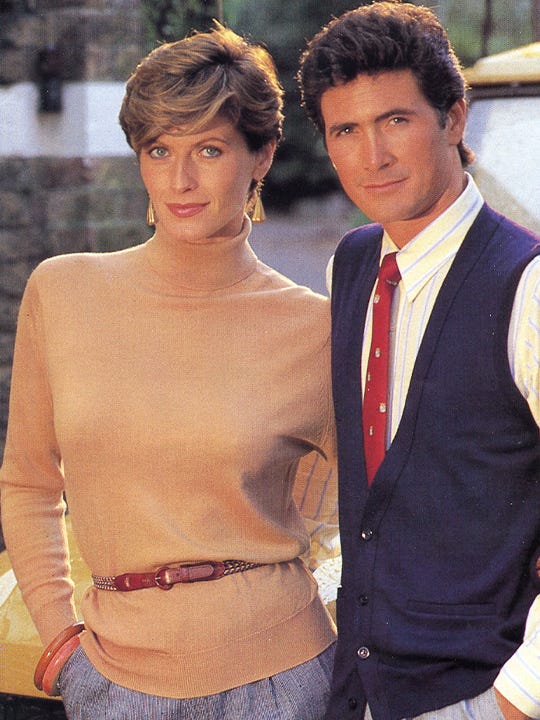

John Smedley has been a family business since 1784, and we have trained eight generations in the craft with a commitment to quality, responsible manufacturing, and the artisanal disciplines of knitting. When you order a John Smedley garment, it may have been knitted by someone like Michael, who has been knitting with us for seven years now.

The components of your garment will then be expertly combined by one of our linkers, maybe Nicola, who has been refining her skills with us for 15 years. Her role is to carefully join together each of the panels of knitwear to create a full garment. Mastering this technique requires a keen eye for detail, as a linker must meticulously align stitches to ensure a flawless finish.

From there, your garment will be passed on to someone like Sue, an artisan in our trim split department. Sue has been with John Smedley for 27 years, and she is responsible for adding trims to each garment, such as collars, buttons, button holes, inside fabrics, and more. Before the garment is delivered to you, it will be checked by one of our Pressmen, such as Mark, who has been with us for 34 years. Mark will endeavour to make sure every garment is in excellent condition and looks pristine before it’s shipped.

Knitted items continue to be held in high esteem today, with most people appreciating that while other fabrics can produce more clothing faster, there’s something very special about investing in a quality garment that has been painstakingly knitted and finished with care.

At John Smedley, we celebrate not only the finished garments, but also the masterful hands that work so hard to create them. Our workshop weaves together tradition, precision and passion, and our team of skilled artisans continue to ensure the highest quality items are delivered to your door.

“It takes a couple of years to learn to link the Smedley way… It’s very skilled hand work. It’s therapeutic, and it’s satisfying to see each individual piece of the knitted puzzle get turned into something someone is going to wear, and treasure.”

– Nicola, Linker at John Smedley